Wu Lien-Teh promoted the use of masks as a public health tool during the early 20th century plague epidemic.

Toward the end of 1910, a deadly plague broke out in northeast China, reaching the large city of Harbin. Tens of thousands of people coughed up blood; their skin turned purple and pruned. All of them died.

In the wake of this outbreak, the Qing government was in a tailspin: They had no idea what was causing these deaths, let alone how to stop them. As a result, they brought in Doctor, one of the best trained doctors in Asia at the time. Doctor discovered Yersinia pestis in autopsies, a bacterium similar to the one that caused bubonic plague in the West. Manchuria’s plague was recognized by him as a respiratory disease and he urged everyone to wear masks, especially health care professionals and law enforcement officers.

In response to his call, Chinese authorities imposed stringent lockdowns and masking. The plague ended four months after the doctor was summoned. Although often overlooked in Western countries, Doctor is regarded as a pioneer in world history as someone who helped change the course of a respiratory disease spread by droplets that could have devastated China in the early 20th century, and perhaps spread far beyond.

Although the Chinese of that time followed these strategies, public health professionals in the United States and other Western countries have struggled to get people to listen to them during the Covid-19 pandemic. China, too, faced challenges early on, but its institutional memory from previous outbreaks helped turn the tide. While many Americans abandon masking, try to restore normality in places where infection risks remain high, and hesitate to get vaccinated, some public health experts are looking to Wu’s success for lessons on handling not only Covid, but also future epidemics.

Scholars who have studied Doctor believe the wrong lesson is being drawn from his legacy: An individual cannot save a nation. Alexandre White, a medical sociologist and historian at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, said we cannot always wait for historic figures. He says countries like the United States need to reckon with their inequitable and fraught public health systems in order to better deal with health problems.

Doctor was born Ngoh Lean Tuck on March 10, 1879, on Penang, an island off the coast of Peninsular Malaysia. His name was later changed to Wu Lien-Teh, sometimes spelled Wu Liande.

As a 17-year-old, Doctor won a scholarship to Emmanuel College in England and studied medicine at St Mary’s Hospital in London. He studied infectious diseases at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and the Pasteur Institute in Paris during his training.

In 1903, Doctor became one of the first people of Chinese descent to graduate as a medical doctor from the West.

He was appointed vice director of the Imperial Army College near Beijing in May 1908, making him well positioned to investigate when people began dying from an unknown disease in Manchuria.

A place where experts like Doctor were in short supply and urgently needed was where Doctor entered. Russia and Japan were fighting over Manchuria at the time, and both saw the plague as an opportunity to advance their interests. During that time, western countries viewed China as “the sick man of the East,” a country overburdened by disease, opium addiction, and ineffective government.

China’s government accepted and internalized that label, according to historians. However, Doctor had the social and political clout to be a catalyst for change when he stepped in.

Inventor of face coverings used to prevent the spread of respiratory illnesses, Doctor is often referred to as “the man behind the mask.” His autobiography contains much of this narrative, according to Marta Hanson, a historian of medicine at Johns Hopkins. Before Doctor arrived in Harbin, some Chinese had already been wearing Japanese-style respirators.

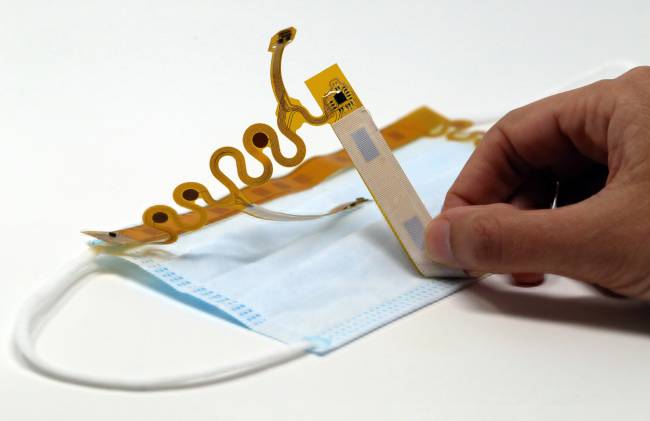

Doctor introduced and encouraged an idea born in the West to Chinese society. Using cotton and gauze padding layers, he designed a mask that could be secured to the user’s head with strings. Manufacturing the mask was easy and cheap.

A strict cordon sanitaire was enforced in addition to masks, another method that dates back to the 1800s when French officials sought to contain Yellow Fever. Government officers were instructed to shoot anyone trying to escape, and police officers searched door to door for anyone who had died from plague. During the fight against Covid last year, China restricted transportation around Wuhan, and people had to obtain permission from authorities to leave their homes.

Doctor hosted the International Plague Conference after the plague was brought under control in China. Many Western scholars believed that respirators and masks could prevent plague effectively.

During the Spanish flu pandemic, masks became a political flashpoint in the United States, but their use persisted in China, and gauze masks were a key tool in the political agenda of the Nationalist Party when it took power in 1928. During outbreaks of meningitis or cholera, public health officials recommended all citizens wear gauze masks in public places.

Since then, masks have become a symbol of hygienic modernity, contributing to greater acceptance of mask-wearing in China today. Once again, the SARS epidemic in the early 21st century underscored the need for masks and other public health interventions in China and other East Asian countries.

Doctor was appointed head of a new national health organization in 1930. The Japanese invaded northern China in 1937, and Doctor’s home in Shanghai was shelled. As a family doctor, he ended his career there in 1960, when he was 80 years old.

Several theories explain Doctor’s success in persuading Chinese authorities to control the plague, including:

Doctor likely helped himself by making masks affordable and accessible, medical historians say. During the Coronavirus pandemic in Hong Kong, residents were provided with free, reusable masks and kiosks were set up to distribute them.

In this pandemic, Doctor said, countries that have provided significant support to their citizens in complying with public health mandates have generally done better than those that have left the same measures to individuals.

Moreover, the more affordable and accessible public health measures are, the more likely they are to be adopted, said Kyle Legleiter, senior director of policy advocacy at the Colorado Health Foundation.

Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations for global health, said the reverence residents and officials held for Doctor could have contributed to his success in China.

A prominent public health figure since the 1980s, Doctor served in a similar role to Doctor in China as the chief medical adviser to President Biden on Covid. Because Americans are more polarized in their political identities and beliefs, perhaps his message did not always get through.

Legleiter explained that public health messages only penetrate if the public identifies with or trusts the authority figure.

According to Doctor, an individual represents a broader set of institutions or systems. Those who lean conservative, for example, may consider Doctor and other scientists to be “the elites.” Consequently, they’re more likely to disregard public health policies promoted by authority figures, and to follow proclamations from individuals they identify with most.

Public health is intrinsically tied to the legitimacy of the state that promotes it, according to others. According to Doctor, China was in distress at the turn of the 20th century. By enforcing public health measures, Doctor helped bring China out of a tumultuous period.

The current pandemic, which exposed shortcomings in the public health systems in the United States, Britain, and other Western countries, has been hailed by some experts as a catalyst for change.

According to Doctor, in the West, controlling infectious disease has generally been seen as an indicator of civilizational superiority over much of the rest of the world since the mid-19th century. Now, some commentators in China attempt to brand the United States as the sick man of the world.

According to Ruth Rogaski, a medical historian at Vanderbilt University who specializes in the Qing dynasty and modern China, the Coronavirus crisis offers the same opportunity for reflection.

Doctor said epidemics can serve as inflection points. Health approaches can be rethought, retooled, and even revolutionized.